Page 153 - Littleton, CO Comprehensive Plan

P. 153

29

OBSERVATIONS FROM INVENTORY

The following observations will be elaborated on through workshop discussions and further use of visuals, especially

as the focus turns to future land use planning during the Future City phase. In the meantime, all of these findings have

implications for how Littleton may adjust its approach to regulating and setting standards for land development and

redevelopment going forward to place more emphasis on desired character outcomes.

1. Entire Character Spectrum. Nearly all elements of the community character spectrum may be found in Littleton,

which is part of what makes it a much more interesting experience than many suburban communities.

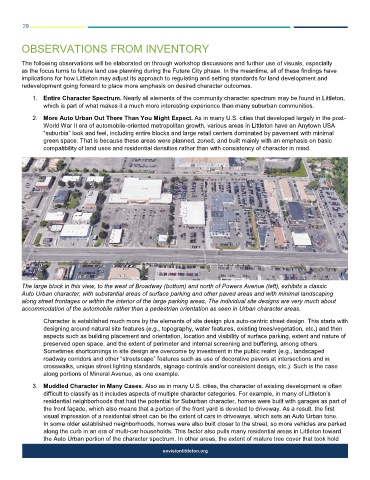

2. More Auto Urban Out There Than You Might Expect. As in many U.S. cities that developed largely in the post-

World War II era of automobile-oriented metropolitan growth, various areas in Littleton have an Anytown USA

“suburbia” look and feel, including entire blocks and large retail centers dominated by pavement with minimal

green space. That is because these areas were planned, zoned, and built mainly with an emphasis on basic

compatibility of land uses and residential densities rather than with consistency of character in mind.

The large block in this view, to the west of Broadway (bottom) and north of Powers Avenue (left), exhibits a classic

Auto Urban character, with substantial areas of surface parking and other paved areas and with minimal landscaping

along street frontages or within the interior of the large parking areas. The individual site designs are very much about

accommodation of the automobile rather than a pedestrian orientation as seen in Urban character areas.

Character is established much more by the elements of site design plus auto-centric street design. This starts with

designing around natural site features (e.g., topography, water features, existing trees/vegetation, etc.) and then

aspects such as building placement and orientation, location and visibility of surface parking, extent and nature of

preserved open space, and the extent of perimeter and internal screening and buffering, among others.

Sometimes shortcomings in site design are overcome by investment in the public realm (e.g., landscaped

roadway corridors and other “streetscape” features such as use of decorative pavers at intersections and in

crosswalks, unique street lighting standards, signage controls and/or consistent design, etc.). Such is the case

along portions of Mineral Avenue, as one example.

3. Muddled Character in Many Cases. Also as in many U.S. cities, the character of existing development is often

difficult to classify as it includes aspects of multiple character categories. For example, in many of Littleton’s

residential neighborhoods that had the potential for Suburban character, homes were built with garages as part of

the front façade, which also means that a portion of the front yard is devoted to driveway. As a result, the first

visual impression of a residential street can be the extent of cars in driveways, which sets an Auto Urban tone.

In some older established neighborhoods, homes were also built closer to the street, so more vehicles are parked

along the curb in an era of multi-car households. This factor also pulls many residential areas in Littleton toward

the Auto Urban portion of the character spectrum. In other areas, the extent of mature tree cover that took hold